Concerning the "spiritual", both the reductionistic dismissal of bad science and the reactive reification of wishful yogis are wrong. A certain ontological revolution is implied, and as it turns out, quite necessary: the objective-subjective dichotomy is a relic of postaxial thinking which must be overcome. There is no such thing as "objective existence", only highly stable points of configuration space, only redundantly confirmed experience which we find so easily communicated that we feel certain must exist just as we describe it, only blockages in our exploration of the unknown, only stupidities which serve us well. On the other hand, there is no such thing as "subjective experience", as though anything could exist in a purely virtual world of nonexistence, purely conditional, purely effect without being cause, as though a oneway checkvalve guarded the gates of the transition from objective to subjective. It's worthwhile studying Spinoza just to get a sense for how ridiculous this ontology is and always has been: his solution was to keep the two planes strictly isolated but magically parallel - and all psychology since has more or less settled for this absurdity. I have no patience for the "mind-body problem", because the assumptions are wrong from the outset: there is no body which exists independent of any experience, nor an invisible mind riding within that fictional boat. The solution is to stop attempting to be so smart, and try being honest about what it feels like to be alive among so many other lives: there are many worlds quivering between illusion and fact, many possible tapestries of overlapping story, innumerable branches of axis mundi, innumerable planes of causality, innumerable possible physics, innumerable possible languages and thus innumerable possible worlds.

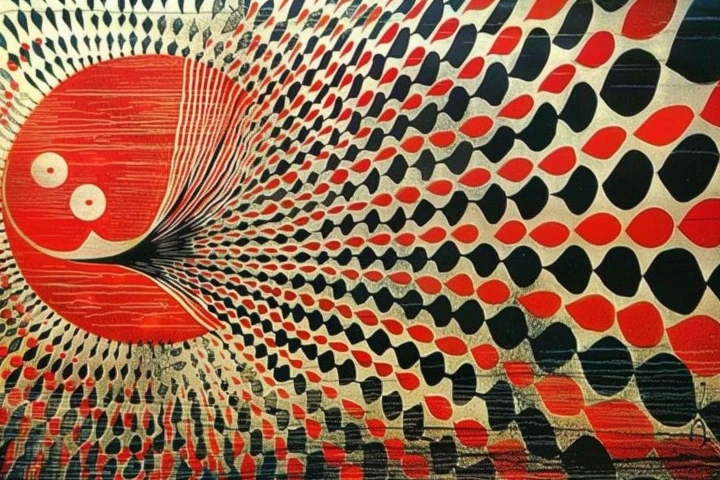

Objectivity is also an illusion. There are no objective phenomena, except that it too is a function of the neural body. Part of the neuromorphic strategy is to collect datum in order to project it onto the inner surface of a sphere, the Merkwelt, such that it can be re-perceived as a coherence, and in that secondary perception is "objectivity". In other words, we begin to "get things right" only after we've confabulated a great deal: most empirical data is merely well-formed prejudice.

Meanwhile, in the implied center of such a projection, which is never actually experienced, is the subjective. Again the experience of objectivity or "reality itself" is not naked perception without the interference of subjective factors - that's impossible - but the re-perception of projected data. It's not at all raw sensory data, but the fabricated coherence of processed perception which gives us a sense of "the object", the "thing in itself", a hard cold reality. When we do approach a raw form, it's generally reported as hallucination, dream, nonsense, or psychosis. And only in reversing the valuations do we begin to experience the nature of experience: it's in this projection and secondary perception routine, that the secret of subjectivity lies. The manufacture of illusion is the most empirically oriented aspect of the story, while the belief in unitary reality is the most delusional. This is finally the perspective afforded by those who meditate deeply and long: what's most real and certain, is that we fabricate the real and certain. The difference I add is only that I insist that we understand every confabulation not as error and tragedy, but as adaptive and the glory of life: there is no "reality itself" from which life's glorious errors go astray, only those glorious errors themselves, making and remaking reality in their wake.

How did we come to this misunderstanding? To what degree is our belief in an objective world of facts, the "Sachverhalt", a biological necessity and to what degree is it a consequence of postagricultural conditioning?

To the city dweller, what's constant? The city, its walls, its law. "Law" as prime metaphor of science: a postagricultural superstition which proves exceedingly difficult to displace.

To the nomad, what's constant? The tribe, its ritual, its myths. Ritual as prime metaphor of pre-axial science: that the world is cast and recast in every ritual invocation, that things are the way they are because of ritual efficacy. One can see this idea still alive in the Rig Veda, the Yijing, and some of the presocratics. What does it mean, to "recast" the world? That the miniature affects the whole, that symbol is power, that reality is a consequence of constituting power, that knowledge and manipulation of that knowledge creates the world.

The idea of an "objective world of facts" therefore, is a consequence of postagricultural conditioning to the persistent lawful city, in which despite all vicissitudes of human frailty, civilization endures: we unconsciously understand nature as the prior civilization, in which primal law reigns supreme above all its silly inhabitants, each defying it as best it can despite ultimately confirming its necessity.

That we have found our way back to an animistic worldview, is just confirmation of how weak the trust in civilization has become. We increasingly find the metaphor of "natural law" to be unconvincing, because we find law unconvincing.

The problem with the objective-subjective dichotomy is that it falsifies experience and leads to ridiculous outcomes. Either the world is composed of asymptotically receding verifiable fact and subjective qualia are meaningless, or almost all of existence is itself an illusion and only an unverifiable monad of self resides in some invisible womb. To both absurdities we say, "नेति नेति - neti neti". This debate is so old that it was driven to its conclusive extremes as early as 600 BC in the Indian subcontinent, and it was the Indian talent for bombast which lead to some of the most profound restatements of Paleolithic wisdom in postaxial terms: the fourfold negation and the doctrine of "dependent coarising" were formulated in response to paradoxes like these.

The important thing is to learn from experience: obviously the world will go on without you, and yet obviously everything you know about this world is conditioned by a perceptual frame you cannot observe. Therefore that's the nature of experience: to be "coarising", to be suspended between irresolvable tension, to be intractable to our logic. Why should we possess the kind of logic which might unravel the nature of experience? Isn't our logic a product of what makes a creature optimally functional in this world, which might involve a great deal of illusion and misunderstanding?

Nietzsche's anti-metaphysics belong here, and is obviously the training in my background that makes my voice in these matters seem oddly at ease with paradox, oddly unconcerned in resolving every logical tension. I learned German in my early 20s just so that I could read him in the original, so intense was my initial reaction: I required three months to read Jenseits von Gut und Böse just because every other page caused me to revaluate everything I'd heard thus far. By the time I'd finished my first taste of Fritz, I had habits of perspective which have only deepened over the years: don't ask, "how does this make sense in its own terms?", ask "how does this make sense as a symptom of humanity?". This obviously risks pathologizing everything, like the bad Lacanians or Marxists do, but the other prerequisite of understanding Nietzsche is something he mostly takes for granted: that you love life, deeply and truly, and would rather find yourself alone and contrary than come away from any dialogue with yourself feeling more wretched and unwilling. In other words, gratitude as method infuses the Nietzschean way: it acknowledges a certain choice in perspective, because it's acknowledged that this fragile and probably illusory choice expresses valuation more than anything else. The key to grokking the sincerity of Nietzsche's approach, that which prevents him from being merely another poser, merely another seductress of intelligentsia, is that he was always and is always a convalescent: it was his acquired genius in psychosomatics, that makes him much more than "philosopher". Read the preface to Die Fröhliche Wissenschaft: the act of thinking was for him an athleticism, something done willfully in order to achieve health, like a yogi does plankpose. I didn't really find my voice until I started hiking daily: your best thoughts should be a song worth repeating, something at least half chanted, something you feel you have a right to know.

Nur allzu leicht wiegen wir uns in dem Wahne, daß die Beziehungen des fremden Subjektes zu seinen Umweltdingen sich im gleichen Raume und in der gleichen Zeit abspielen wie die Beziehungen, die uns mit den Dingen unserer Menschenwelt verknüpfen. Genährt wird dieser Wahn durch den Glauben an die Existenz einer einzigen Welt, in die alle Lebewesen eingeschachtelt sind. Daraus entspringt die allgemein gehegte Überzeugung, daß es nur einen Raum und eine Zeit für alle Lebewesen geben müsse.

We comfort ourselves all too easily with the delusion that the relations of a foreign subject to its environment play out in the same space and time as the relations that connect us to the things of the human world. This delusion is fed by the belief in the existence of one single world, in which all living beings are encased. From this arises the widely held conviction that there must be only one space and one time for all living beings.

Jakob von Uexküll, Streifzüge, §1. Die Umwelträume

The study of animal life is not merely a question of science, it's a reversal of the willful stupidity enforced by civilizational forces: our arrogance isn't merely the hunter's sense of superiority writ larger, it's the fearful envious attitude of the town-dweller toward everything which escapes his form of slavery. The hunter had to understand his prey, which is not the same as empathy, but it does require subjective fluidity at the limit of mimicry and stalking: the tracker's perceptive subtlety is orders of magnitude more "scientific" than the typical flatulent glassy-eyed appraisal of "nature" - which sees everything not clothed nor employed nor speaking a human tongue as probably too stupid to know better.

Consider whether Hume and Hobbes are predecessors - an unembarrassed Scotch skepticism and a very English dourness: the important thing isn't their paucity of joy, but the way they were willing to see nature as something arbitrary, as whim. It's easy for us now, but it was a revolution at the time to think of Nature-with-a-capital-N as unlawful, as unlawful as it can get away with: the fundamental assumptions and ontological implications of something as boring as statistics, has yet to be resolved. Is probability a measure of prior certainty or a limiting factor in the generative functions of reality? Is statistics the artifacts of a limited empirical set or do our methods of approximation express something inherent in the mechanics? My answer is that the question is framed incorrectly: opposing strict determinacy to the profound epistemological critique Nietzsche was heir to, confuses the entire dialogue - and I suspect not unintentionally. There's no reason not to imagine that everything happens with as much "causality" as the whole can muster - in other words that reality unfolds with absolute necessity, but that absolutely no "law" takes place. Which also means that although innumerable possible worlds is the most sensible answer, each of these worlds is just as "determined" as the next.

In "ontology" as in everything else, I try to return to those principles I've discovered for myself, those anthropocentric principles I won with pain. Belief is defined by unbelief: so the application here, is that a single world of facts is not naïvely believed in at all, but is another of those morally charged fictions which apekind finds expedient, a mode of exchange, a handshake. To raise the empty hand in greeting, to feign harmlessness as a sign not of harmlessness but one's investment in the attribution: so I find most of what's called philosophy merely the pedantic refinement of the rituals of social exchange, a marketplace of dated attitudes, a catalogue of costumes which hid someone's motives at some time.

In other words, our little "ontological revolution" is only necessitated by the moral training of a spiritual life, for lack of better terms - we found it so much more advantageous to abandon the belief in a single world of facts, than to tire oneself out defending this doomed castle, someone else's castle after all. Every "single world of fact" is somebody's world: all real estate in philosophy has already changed hands many times, and the task is not finding "god's country" but understanding where you're squatting... Does that sound like the philosophy of an eccentric hobo who picks through the wreckage of the ages? If so I'm fine with that, as long as we understand that we're circling the deeper rationality of our nomad ancestors, trying to unearth their most sensible and enduring latticework of reasons - those perspectives which our instincts deploy inevitably, projected like a solar sail.